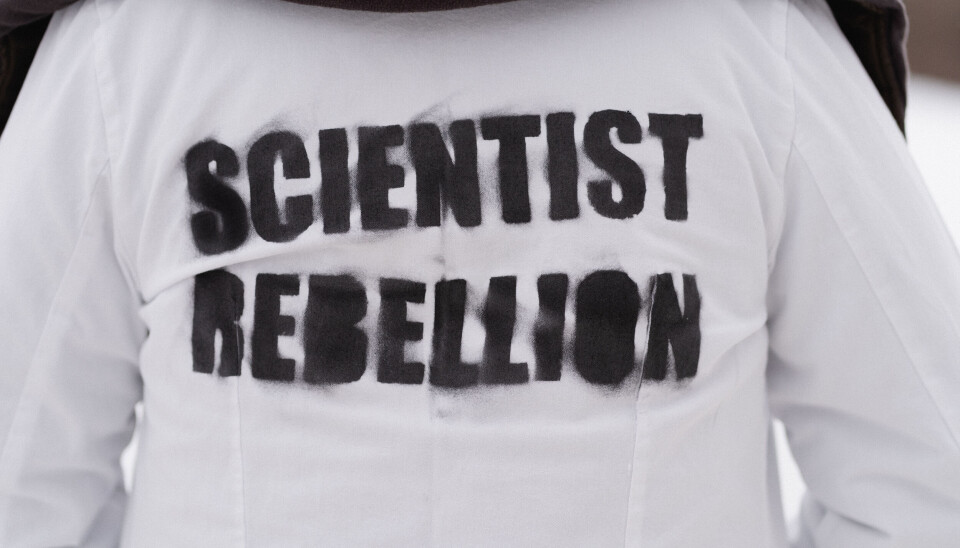

They've jammed the traffic at Elgeseter bridge, been awarded a communication prize from NTNU, and think the ideal of the neutral scientist is medieval. Meet three of the activists from Scientist Rebellion Trondheim.

The activists in lab coats:

– The ideal of neutral scientists is medieval

– Scientists are privileged in the sense that they know things others don't. That's normal, it's their field. But knowledge comes with responsibility. You can't just sit calmly and say «ok, the earth is on fire». You have to send the same message, says Tiffany Tran-Heinerich.

She's from France, a country well renowned for their demonstrations. Yet, it was an exchange year in Trondheim that would turn the master student into an activist.

Thomas Ray Haaland and Angeline Bruls agree. The three of them are part of a network of activists dressed in lab coats called Scientist Rebellion. Haaland joined largely because he at the time saw much of the debate on environmental activism revolve around the activists´ lack of credibility.

– Scientists coming in saying that we have the same demands as Stopp Oljeletinga, that they know what they're talking about, it changed the conversation quite a lot. If scientists can contribute to the environmental movement being taken seriously, I think that's good. It was a “no-brainer” for me.

Haaland is a postdoc in evolutionary biology who researches how birds respond to extreme weather events. Bruls is writing her PhD on how biodiversity changes across different times and locations, but the Dutch scientist also feels the urge to act now.

– Research is quite a slow process. By being part of Scientist Rebellion, I feel like I´m doing something here and now, something more active on the side of my research work.

– It's us and Saudi-Arabia

Scientist Rebellion (SR) is an international network of scientists and academics seeking to convey the gravity of the climate- and nature crisis, and the importance of acting now. Non-violent civil disobedience is a frequently used strategy.

SR started in 2020, and the Trondheim group was founded during springtime in 2022. In Trondheim, there are somewhere between 30 and 40 active members; mostly scientists and some students.

Haaland paints a picture of an organization with horizontal structure, without a leader or binding obligations. This partly as a philosophy, and partly due to practical reasons.

– Organizing crime is kind of a really bad thing to do, but that's not what we're doing either. We´re individuals acting out of conscience. Of course, there needs to be some system for the sake of cooperation, but no one is telling others what to do.

Tran-Heinerich explains that SR Trondheim has three main goals: phasing out oil and gas, teaching about climate change, and mobilizing people to act.

– We´ve seen that Norway particularly has a problem of climate change denial. So that's something we're trying to target, she continues.

The activists refer to the EU study from 2022, which revealed that one out of four Norwegians don´t believe that climate changes are caused by humans. Haaland adds:

– Norway is by far the worst in Europe. It's us and Saudi Arabia. So we have a job to do.

Climate cafés and civil disobedience

And the method? SR is probably most famous for their demonstrations and civil disobedience. Maybe you were one of those stuck in traffic when some scientists «slow marched» over Elgeseter bridge in November last year? Or maybe you saw them block the road in front of Samfundet?

Haaland emphasizes that the actions are only the tip of the iceberg of their activity.

– The actions are sort of the culmination of what we do. Much of it is mobilizing professors and students. Then there's also the teaching, such as organizing talks and climate cafés at Antikvariatet.

Further, he explains that they work a lot in the scientific sphere. They publish scientific articles about the theme, but they also mobilize people at scientific conferences:

– We´ve actually done training in civil disobedience at scientific conferences, which was quite cool.

Presence in the media and social media is also part of it. It's the communicative and educative work (and not the civil disobedience), which was the reason for the Faculty of Natural Sciences at NTNU awarding them the “Communicator of the year” in january.

– For me, this signaled that the faculty acknowledges the work we do, that they take it seriously and support it, Bruls says.

Haaland says that scientist colleagues at NTNU have mostly been positive about the activism, and that there has been more resistance from private research organizations. He still thinks it's big that the faculty awarded them the price:

– There was definitely a lot of debate about this prize, so I think it was quite “ballsy” of them to actually do it.

Would rather be at home than in prison

Award or not, civil disobedience is still necessary, according to Tran-Heinerich:

– We're not out in the streets for our own amusement. Those getting arrested would rather be at home than in a cell. The problem is that this attracts the most attention to the case, especially when someone gets arrested.

Bruls points to this being effective in the civil rights movement in the United States and India, and in feminist movements. She hopes the environmental movement can see the same effect. Yet, she admits that it doesn't come all too natural for her.

– I´m one of those who always waits for the green light before I cross the road. I never do anything that's not allowed. So it's quite interesting to make a conscious choice of doing something I shouldn't, according to the law.

Tran-Heinerich and Haaland describe the actions and civil disobedience as a mix of positive and negative stress.

– The demonstrations are quite empowering, even though you’d wish they weren’t needed, of course. At the same time it’s very easy to feel that it’s the right thing to do, Haaland concludes.

Is it possible to combine activism and science?

– In many countries around the world you can´t protest or be affiliated with someone protesting illegally. In Norway we actually have this privilege, Haaland says.

The activists tell us about how scientists in other countries who lost their jobs because they were activists. They themselves think it should be fully possible to be both a scientist and activist. Bruls states that the ideal of a neutral and objective scientist is outdated:

– I´ve learned that the idea of scientists needing to be neutral comes from the Middle Ages. The scientists back then were also monks who had to live a «pure» lifestyle to secure a pure connection with God.

She continues:

– Of course, my scientific work needs to be neutral and I wouldn't make up data, but I don't think that limits me from voicing my opinion outside of work.

Haaland links this to freedom of speech in academia, which has been heavily debated at NTNU this winter.

– Limiting those who know best, not letting them communicate in the way they see as appropriate, that's not good. I think it's very important to have this conversation; for me it is obvious that we´re not doing anything wrong.

When asked if they´re worried about their research being interpreted as research with an agenda, Tran-Heinerich emphasizes that full objectivity is impossible.

– I mean, everyone has an opinion. You are never completely objective. But as long as scientists follow scientific methods and are transparent in their research, I don't see why this should be a problem.

She also points to other research being tied to ulterior motives:

– I guess it's a bit similar to when your research position is sponsored by Equinor. You can´t be completely objective in that sense.

– The oil money is everywhere

When asked what they think about the NTNU cooperation with Equinor, they laugh a bit, before Haaland replies:

– Many biologists are against it. We also have several geologists in our group working closely with Equinor. They agree with us, but at the same time they can't come out and say anything about this, because Equinor would take it badly. There's a lot of money in this.

Consequently, the scientist-activists see themselves as a counterbalance to other strong interests.

– The oil lobbyists and oil money are heavily present at NTNU, Samfundet and in student organizations. They are everywhere, Haaland says.

They have also followed the debate about oil sponsorship at Samfundet. As late as February this year, the Samfundet members in Storsalen voted against a resolution that would stop further cooperation with Equinor. Haaland thinks it´s concerning that it seems difficult to do culture, sports and student volunteering without the big oil sponsor.

– At the same time I understand the students and that they don't want to lose UKA as they know it. For me, it's a big symptom of a big problem.

Medicine against eco-anxiety

Haaland mentions another symptom of the big problem, which is the growing phenomenon of eco-anxiety. He thinks that professors and instructors being honest about their emotions concerning the climate crisis could be healthy for everyone.

– I think it can contribute to students and youths understanding the crisis better, but also becoming better equipped to tackle their own climate anxiety.

At least this has been helpful for the activists´ climate anxiety. Tran-Heinerich sees the activist bubble as a weekly highlight:

– When you constantly hear and read about everything going wrong, about war and environmental destruction, it helps to enter a bubble with people who want to make a difference. It's like medicine for me. A mental medicine.

Haaland confirms that Tran-Heinerich is not the only one self medicating with activism:

– It's like a medicine against hopelessness. When we ask people why they do this, they often talk about having walked around with a feeling of hopelessness. Then they realized that this might have a tangible impact. It brings hope.

ALSO READ: Be our guest!