In a hall in the Trondheim Library, a few NTNU academics want to prevent a genocide

Indians at home and in Trondheim are terrified of what is happening to their country.

– We are just a small group of people who have either been in India for the last few months, or followed the situation through the media, and felt knowledge needed to be heard in Norway. Especially about the police brutality facing institutions of education. Universities like NTNU should take a stand, considering what institutions in India are facing, Prerna Bishnoi says.

She is an artist who also teaches at KIT NTNU. She is one of two people speaking at the meeting titled “India Resists: The Rise of Fascism in India”. Held by a group of Indian expatriates with ties to NTNU. In The Magisterial Hall, on the second floor of the Trondheim Municipal Library, a handful of people are gathering. Some Indian, some Norwegian. A Hindi version of the Italian folk song “Ciao Bella” plays in the background. Adopted by resistance fighters combating fascism in Italy during the Second World War, today it is an anthem of resistance to totalitarianism in an entirely different time and place.

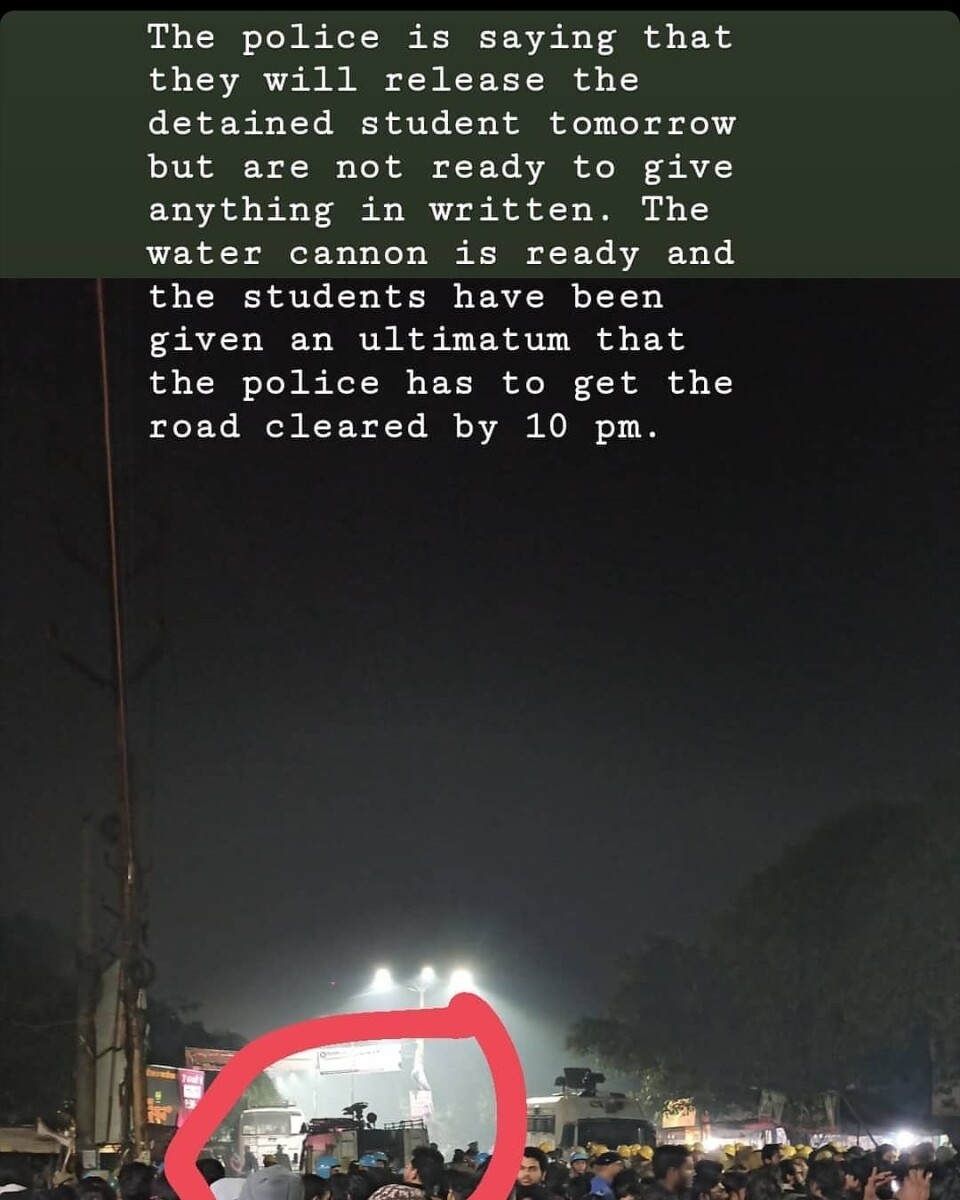

Meanwhile, in India, protests and meetings are ongoing, and have been for several months now. For many, students protest, collective action, and the violent response of the government has become almost routine. Law student Afif Khan attends Aligarh Muslim University in the region of Uttar Pradesh, and Shivangi Pandey studies English at Jamia Millia Islamia University in New Delhi. Both universities have long had protests, and both have been stormed and brutalized by the police.

– I was at the campus when violence was relatively controlled. That’s the way it is now. If there is not an open fire at the university, we just think “This is fine, everything is normal”. The next day I texted my friend who was at the university if they needed anything from off-campus, and got the reply: “Opened fire, don’t come, stay safe”, Shivangi says.

Fear of an Indian nazism

This was on the 15th of December 2019. Police opened fire on students of Jamia Milia peacefully protesting, wounding hundreds. Less than a week before, on the 9th, the Home Minister of India, Amit Shah presentented a controversial new citizenship law. The CAA, or Citizenship Amendment Act. Two days later it passed through the Indian parliament. It gives a path to acquiring Indian citizenship to religious minorities emigrating from the muslim majority countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan.

While the government claims this is benevolent legislation, simply expanding citizenship, it quite explicitly excludes the muslim population. For the first time, the constitutionally secular state of India will have its citizenship determined based on religion. This comes around the same time as the rollout of a National Register of Citizens in the state of Assam, designed to identify and detain illegal immigrants. It has later been proposed to roll it out across India. Proving citizenship has been shown to be difficult, especially for minorities and the poor. People have essentially been forced to prove their citizenship, and the majority of those left off the list of citizens are muslims. With several illegals dying in forced detention centers, the aforementioned Home Minister, Amit Shah, referring to migrants as ‘infiltrators’ and ‘termites’, and muslims murdered by gangs of far-right sympathizers, protestors are coming to fear the worst. To Afif Khan, the situation is all too reminiscent of fascism, and even nazism of the past.

– You have the hero worship of Narendra Modi. There is consistent attack on muslims, like there was with jews in Germany. They are turning citizens into non-citizens and forcing them into detention centers. These detention centers are being funded by public Indian tax money, and with the economic problems I fear people will begin asking why we are spending so much money on this. If they cut funding things will only worsen, with starvation, suicides or in the worst case scenario detainees being killed, he says, although somber, it is also with the matter-of-factly tone of someone within the field of law.

In Europe, many are understandably hesitant to draw the parallel of nazism. However, one lesson one can draw from the death camps: The eradication of the later war years was not planned from the start. It evolved from the circumstances Germany found itself in. It is this perverse logic of fascism that Afif fears will grip India. The fact that the ruling party, BJP, sprang out of the paramilitary group RSS, which openly admired Hitler and Mussolini during The Second World War, makes the comparison seem more apt as well.

Stages of genocide

Back in Trondheim, these are the same fears shared by Prerna and her fellows. They talk about the Ten Stages of Genocide, developed by Dr. Gregory Stanton, the founder of the organization Genocide Watch. These are the ten stages by which a genocide happens as identified by Stanton, beginning with ‘classification’ of ‘us versus them’, and ending with ‘denial’ that it ever took place. When briefing the US congress at the end of last year, Stanton said India was at the eighth stage of ‘persecution’, the one just preceding the ninth of ‘extermination’. When I ask Prerna how likely she believes this is, she has difficulty answering.

– I just hope it will not happen. It is hard to even think about. I just don’t know how to answer something like that, she says hesitantly.

By this time the small group has left The Magisterial Hall and Trondheim Library behind. Now holding a small demonstration in the trade street of Nordre. The protestors have brought a few Indian flags, as well as some placards carrying messages of tolerance and democracy. The sound of “Do You Hear the People Sing?” from Les Miserables and “I Want to Break Free” by Queen is occasionally interrupted by a few short speeches.

– We are so worried about the people back home. I have a friend at one of the universities that were attacked, and right now they are facing so much uncertainty about the future. While protests are organized every single day back home, there is so much fear, because the police try to stop them, says Musab Khalid Naqeeb.

Together with Prerna, he held a facts-oriented and sober presentation earlier at the library, their academic background shining through. But now, out on the street, divorced from the powerpoint, facts and figures, the fear of seeing their home turned into something horrific is apparent.

– When everything started happening, because I have family back in India, my first thought was ‘when will the internet be shut down in my city?’. The moment that happens, I will not be able to contact them. That scares me as well.

Internet shutdowns has been another regular tool of the Indian government. Prerna talks about the internet being shut down for days in Delhi, where her parents live. In the muslim majority state of Kashmir, it was shut down for months. In Kashmir, they didn’t just lock down the internet, though, they locked down the entire state. Still there are militarily enforced curfews. With the world now being forced inside their homes due to fear of the Covid-19 virus, perhaps one is able to understand just a small part of what the Kashmiris have been going through for months.

A loss of power for the higher castes

So what is the appeal of the Indian far right, and how does it stay in power? While Shivangi may have progressive views, not all her family does.

– I am from a very right-wing family. My father will sit down at the table and talk about how the mass rape of women in Kashmir was justified and should happen more. My uncle, for instance, who is also right-wing, would say this is something that shouldn’t happen in a decent society, she says.

Shivangis family is part of the Brahmin, the highest caste of India. She believes much of the appeal of the hindu nationalism comes from a loss of power.

– You can be a working class Brahmin, who does not have much. Then it is easy to feed you the idea that the reason you are not richer is not because the government has failed you, but because of a muslim invasion.

According to Afif, Modi rose to power on a platform of changing a system run by a corrupt predecessor. By many he was viewed as a reformist, who was going to bring development to India.

– Today, the economy is not doing very well. The growth rate has slowed, banks have been shut down. Even the centrists and center-right voters understand now that he is not the promised reformer. So, the new narrative is that we have to get rid of the immigrants, he says.

Still hopeful

However, in spite of everything, both Afif and Shivangi still believe there is hope that India can push back against extremism and hatred. They see this hope largely in the constitution.

– Indian roots are constitutionally very strong. You do see the courts pushing back on some things, Afif says.

For Shivangi there is a historical ring to this situation. The nation of India started by resisting the injustices of British colonial rule.

– What gives me hope right now is what we are doing right now. Resisting an oppressive regime is how this country started.

Back on the streets of Trondheim there is also hope. While a demonstration of about twenty people trying to change policy in a nation of 1.3 billion might seem like a tiny drop in a very large ocean, the feeling here is that everyone has to do whatever they can. For Afaz Ahmed, postdoc in energy and process technology at NTNU, it all has to start somewhere.

– I feel good, actually. The people who came, they didn’t have to come. They are not themselves affected by what happens in India. We will do more later, but now I am thankful to the people who came out and supported us.

In the time after this, all of India has been locked down because of the Coronavirus, after it spread there as well. This has made it difficult for protests to go on and many are looking at alternative ways to continue resistance. These problems have not gone away, for instance, those without documents have problems receiving medical assistance. For a nation that was already mired in uncertainty, the uncertainty is now only growing.